By Kenneth Grimes

On June 30, George E. Brantley retired after 43 years of stewardship of the Hope Center. The early childhood facility on 34th Avenue and Elizabeth Street and the facility for developmentally disabled adults on 35th Avenue and Holly Street are the largest non-profit organizations in Northeast Denver. More importantly, the Hope Center has been a haven for thousands of children and adults, receiving quality service from a recognized institution. Hope Center has consistently earned National Accreditation for the Education of Young Children and the Commission of Rehabilitation Facilities. For eight of nine years, the center has received four out of four stars from Qualistar, an early childhood education certifying organization.

On June 4, family, friends, and staff packed the Denver City Council Chambers to watch Brantley receive a proclamation that stated in part, “Whereas Hope Center is celebrating 45 years in existence and salutes the man that made the center what it is today, and whereas George Brantley has been an African American that has made all people proud, we unanimously present this proclamation to a man of distinction, George E. Brantley.”

Brantley’s rise to distinction wasn’t always an easy journey. He was hired as a teacher when the organization was only 2 years old. He remembers having nine “retarded” children in his first classroom. He said, “Thank goodness we have come up with kinder, gentler ways of referring to the developmentally disabled as they are called now.”

“I remember each one of those children. That classroom was my world and I loved it. I was having so much fun teaching, I said, ‘I can’t believe they’re paying me to do this,’” he said.

Recalling going to a petting zoo with his troupe of young learners, he laughed, “They gave us these little packets to feed the farm animals. I had this one autistic child who called me ‘Brantley.’ I felt this tug on my shirt and see this little guy with these big eyes and he says, ‘Brantley, Brantley, I’m tryin’ ta feed this goat but he’s eatin’ my sweater.’ There were so many moments like that that stick with you over the years.”

In 1965, Brantley was called to head the fledgling organization as executive director, a position he has never taken lightly.

“To be frank with you,” he confided, “It was a real transition in the beginning. I still loved my little classroom world. Administration operated in the basement and the classes were upstairs. As often as possible, I would go upstairs and let a teacher take a break while I taught their class. After a while though, my administrative duties took more and more of my time so that when I did go to the classroom, it became a scary thing. Teachers have to be prepared or suffer the consequences. Children will let you know with their behavior when you’re not prepared.”

Brantley became a full-fledged administrator with a board of directors, and suddenly his world became much larger. He told how his administrative assistant, Lorraine Faulstich, had a youth in the program and was also on the board.

“Technically, she was my boss and I was hers, and then she was also the parent of a client I served,” he smiled in reflection. “Mrs. Faulstich was with the agency for 17 or 18 years."

He learned a lot from her, including a perspective about serving the needy. He described how there had been a parent receiving a scholarship to support her children participating in the program.

“She drove this Cadillac, I think it was, and staff questioned why she should receive assistance from us if she was able to afford such a nice car,” but Brantley was aware of her financial situation.

He said it was then he adopted one of his guiding principles: we never know what people need to maintain their dignity. We do a disservice to people when we judge them by our standards.”

Brantley said his biggest challenge as a leader was coming to the realization that his dedication had to be to the agency sometimes at the expense of the individual.

“The most difficult thing was to have to let people go whether it was because of funding issues, qualification issues, or personal issues. In each case, we’ve never been so large where you don’t know the people who work for you on a personal level. Often you know their families, their personal aspirations. You know the probable impact letting them go will have on them and on their families. Those times weigh heavy on your heart.”

Major challenges confronted Brantley and Hope Center during the volatile years of the 60s and 70s. Rose Kennedy, mother of John F. Kennedy, had a daughter with Down syndrome and instigated a federal law shifting the primary source of care and education of children with disabilities from community-based agencies to public institutions. Many parents, however, weren’t satisfied that children and adults only had institutionalization as an option. They wanted them to be eligible for the same advantages as anyone else. Normalization policies were legislated that included making schools available to people with disabilities.

Ironically, Dr. Wilford Keyes, the father of busing for integration in Denver, was also one of the heads of a center for the developmentally disabled. Omar Blair, who is known from having the Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library named after him, was president of the school board during those times. While he and Keyes advocated for educational equality in Denver, “Hope Center, Laradon Hall, Adams Industries, and other community-based programs were fighting for their existence,” said Brantley.

The shift from community-based to institutional service forced a number of agencies out of business. It was Brantley’s tenacity and competitive nature that kept Hope Center in operation.

“It was fortuitous that those heading the most established community-based agencies were African American, as were those leading the movement for equal opportunity and inclusion,” Brantley said, adding that public schools and institutions were receiving federal funds, but didn’t want to distribute them equitably.

“Public schools didn’t have trained or experienced teachers to work with our populations so they started raiding our agencies, actually sending people to make visits to see how we performed our day-to-day business, and then recruited our staff, offering them more money than we could afford to pay,” Brantley explained. “If we were to survive, we had to be eligible for state funding and we had to find our own niche, which in our case we determined to be working with early childhood and adults over 18, especially since the public schools were obligated to serve K through 18. I’ll tell you, it was a battle to survive.”

Hope Center did survive, according to Brantley, by engaging fully and smartly and “consistently offering the best quality services possible.”

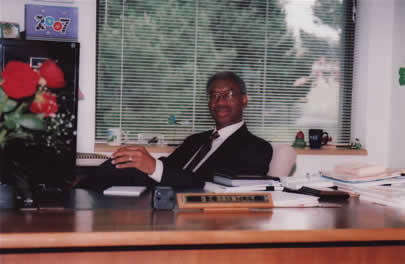

Brantley had a ceramic paperweight in his office that stated, “If you are not the lead dog, your view is always the same.”

He said he has tried to live by that quote, always striving to be in the lead and moving to the top of the mountain.

“This is the reason we went for accreditation even when it wasn’t required. We knew that it would stimulate us to do our best. Only now are others being expected to seek certifications and standards that we have maintained for decades,” he said.

Hope Center also got into the business of purchasing dilapidated grocery stores and turning them into quality facilities.

“Whereas neighborhoods had to put up with eyesores that degraded their value, we gave our neighborhoods facilities that served to upgrade value and to stimulate the economy. Prior to that, we were the vagabonds of the early childhood and developmentally disabled industry, always in flux, always having to move for one reason or another. I declared to myself, ‘We need a home!’” he exclaimed.

One of his board members brought an unused and dilapidated former Safeway store on 35th Avenue and Holly Street to his attention.

“Purchasing a facility was sort of a new paradigm for a nonprofit such as ours. To be frank, my board was aware that they could be liable if we failed to make our mortgage. They were adamantly against the idea,” Brantley said. “I recruited a Board member who knew what was possible from purchasing our first building. He was able to help me share the vision. We purchased the facility. If I had my way, we would have purchased the entire block at that time.”

He revealed that their mortgage was over $2 million with renovation costs, but they paid it off in about seven or eight years, much to the board’s disbelief, according to Brantley. It was not long after that, another old, dilapidated store was brought to Brantley’s attention as a possibility for an early childhood center.

“It was a little easier to make the case for that building,” he said.

The latest challenge for the Hope Center involved helping people see that the agency’s mission to serve individuals with special needs includes the gifted.

“I had read the Bell Curve by Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray,” Brantley said of the controversial book that connects intelligence with American life and with race.

Brantley wasn’t purporting the notion that certain races may be genetically superior as implied in the book, but “if beings from Mars observed our peoples here in America, they might come to the conclusion that African Americans only habited the left end of the bell curve. I knew that didn’t have to be the case,” he said.

Brantley believes that setting high expectations is the way to enact change, and society wasn’t doing enough to identify gifted individuals, especially African Americans. His board wasn’t certain such an effort fit within the agency’s mission.

“I recruited a board member again, who knew what I was seeking to do and could provide evidence to support the vision I wanted to share,” he said.

Hope Center established the HOPE Academy for Gifted Children and has remained dedicated to finding and grooming gifted children early. Brantley believes that “the greatest waste of a natural resource is the neglect of the brain of a gifted child.”

He stated that “many gang leaders in prison are probably gifted. It takes heightened communication skills, innovation and extensive problem-solving capabilities to lead others as they do. Gifted individuals often take risks for a variety of reasons, including curiosity and just to use their extensive abilities, their smarts.”

Finally, Brantley believes that leaders must always plan and posture for the future. In his office, he has an architectural rendering for HOPE Academy, a school to maximize opportunities for people with special needs. He is passionate about the responsibility we all must take to “let the candle shine,” in the lives of children, and adds that “Parents have to stay engaged.”

He described reading a study conducted by Betty Hart and Todd Risley in their book entitled Meaningful Differences. The study shows how poor, lower-class families, according to fiscal measures, have children with vocabularies of three thousand to five thousand fewer words than children from upper-middle-class families.”

He further explained, “The difference is in how parents communicate with their children. I’ve seen parents who mostly communicate on a survival level: ‘No!’ ‘Stop that!’, ‘That’s hot,’ ‘Keep away,’ versus giving explanations that the child can understand. One time I watched this parent that was upper middle class talk with her child while driving. She talked from the moment she got in her car to when she got to her destination. In fact, the child fell asleep at one point and she was still talking. And, this isn’t an isolated instance. Our parents must step it up. Kids that are behind find it very, very difficult to catch up, because those children that are three thousand to five thousand words ahead are not standing still waiting for others to catch up. In fact, that additional vocabulary is opening up opportunities for advancement at an exponential pace.”

During Brantley’s recognition by the city council, many spoke about his wisdom and about how he had been a mentor and elder statesman in the community. A careful steward, he is leaving the agency in the capable hands of Gerie Grimes, who has served Hope Center as Business Manager and Deputy Director for 25 years.

Return To Top |